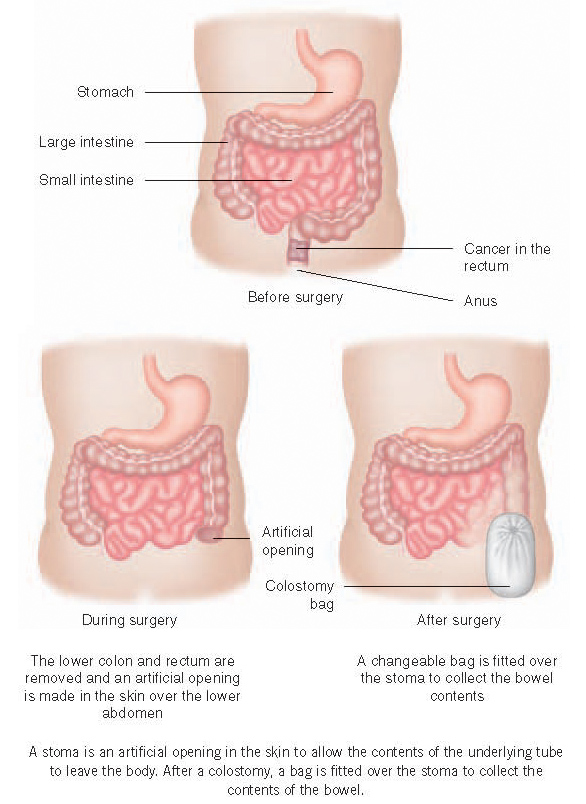

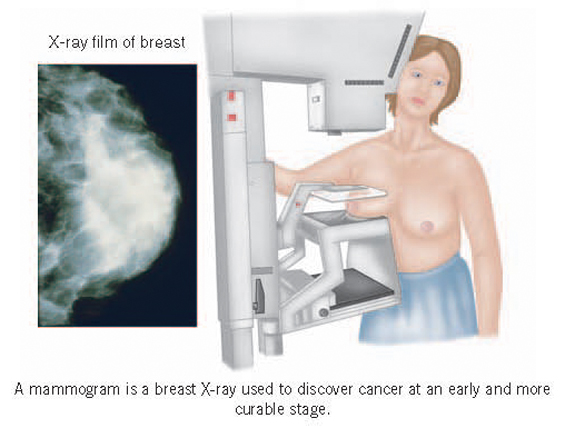

Some useful web-sitesThe NHS provides comprehensive information and useful links at NHS Choices:http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Cancer/Authoritative information and various kinds of other support are provided by many other organisations including:American Cancer Society: http://www.cancer.org/Comprehensive information.Bowel Cancer UK: http://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk/ Information and support.Brain Tumour Charity: www.thebraintumourcharity.org/Information and support.Breast Cancer Care: http://www.breastcancercare.org.uk/Specialist breast care nurses provide practical advice, medical information and support to women concerned about breast cancer.Volunteers who have had breast cancer themselves assist in giving emotional support to cancer patients and their partners.British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy:http://www.itsgoodtotalk.org.uk/Provides a directory listing counsellors and the types of problems for which they offer counselling.Enquirers can be referred to an experienced local counsellor.British Red Cross: http://www.redcross.org.uk/Help with mobility, including loan of wheelchairs and escort services to and from hospital.Children with Cancer UK: http://www.childrenwithcancer.org.uk/Information for children and their families.Cancer Research UK: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/Comprehensive information from the world’s largest cancer research charity.Carers UK: http://www.carersuk.org/Information and support for carers..Carers Trust: http://www.carers.org/Information and support for carers.Colostomy Association: http://www.colostomyassociation.org.uk/Information, support and advice.Cruse Bereavement Care: http://www.cruse.org.uk/Information and support.Kidney Cancer UK: http://www.kcuk.org/Information and support.Leukaemia & Lymphoma Research: http://leukaemialymphomaresearch.org.uk/Information on leukaemias, lymphomas and related conditions.

Leukaemia CARE: http://www.leukaemiacare.org.uk/Information and support to people with leukaemia, lymphomas and related conditions.Lymphoedema Support Network: http://www.lymphoedema.org/Information.Lymphoma Association: http://www.lymphomas.org.uk/Information and support.Macmillan Cancer Support: http://www.macmillan.org.uk/Information, financial and other support for patients and their families.Marie Curie Cancer Care: http://www.mariecurie.org.uk/Runs Marie Curie hospices and provides a community nursing service day and night.National Association of Laryngectomee Clubs: http://www.laryngectomy.org.uk/Information and support for people with a laryngectomy and their carers.National Cancer Institute: http://www.cancer.gov/Comprehensive information from the institute which coordinates the National Cancer Program in the USA.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]: http://www.nice.org.uk Detailed guidance on how best to manage a wide variety of conditions and reports on the clinical and cost-effectiveness of many individual medications and other treatments. This is all based on a very rigorous assessment of the available evidence. Oesophageal Patients Association: http://www.opa.org.uk/Information and support for patients with oesophageal and stomach cancer.Pancreatic Cancer UK: http://www.pancreaticcancer.org.uk/Information and support.Patient.co.uk: http://www.patient.co.uk/Information on most types of cancer.Penny Brohn Cancer Care: http://www.pennybrohncancercare.org/Formerly known as the Bristol Cancer Help Centre, the centre offers complementary care intended to address physical, emotional and spiritual needs.The components include relaxation, healing, visualisation, counselling, diets, meditation, music and art therapy, and support is also given to other family members and carers.There are residential and single day courses.Charges are made for services, but discretionary financial assistance is available.Prostate Cancer UK: http://www.prostatecanceruk.org/Information and support.Relate: http://www.relate.org.uk/home/Advice and counselling for people with emotional, sexual or other problems in their relationships with spouses and partners.There are branches throughout the UK.Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation: http://www.roycastle.org/Information and support.Royal Marsden: http://www.royalmarsden.nhs.uk/Comprehensive information from London’s world renowned cancer hospital.Sue Ryder: http://www.sueryder.org/Has homes and day care centres caring for patients with many different disabilities and diseases, including cancer.Services include long-term care, respite care and support at home.Urostomy Association: https://www.urostomyassociation.org.uk/Information, advice and support on issues such as appliances, work situation and marital problems.IRELAND Irish Cancer Society: http://www.cancer.ie/Information on all aspects of cancer, home care, rehabilitation programmes and support groups.Cancer Focus Northern Ireland: http://cancerfocusni.org/Information and support.SCOTLAND Cancer Support Scotland: http://cancersupportscotland.org/ Emotional and practical support.WALES Tenovus: http://www.tenovus.org.uk/Information and support in English and Welsh.