Drug treatments

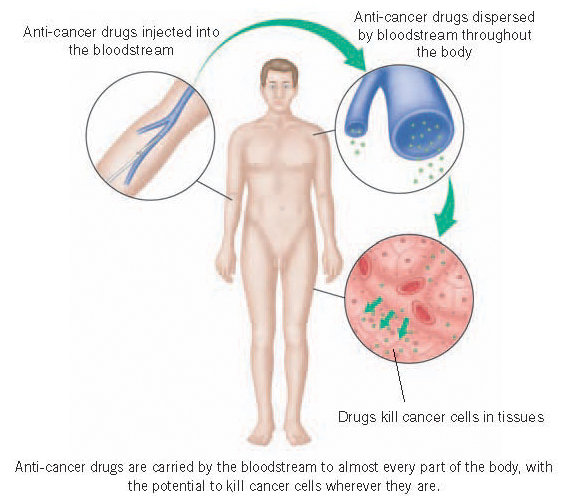

Unlike surgery and radio-therapy, drug treatment is ‘whole body’ or ‘systemic’ treatment. Anti-cancer drugs are carried by the bloodstream to almost every part of the body. Thus it is possible for drugs to kill cancer cells wherever they are. Drugs are particularly useful, therefore, in the treatment of cancers that have spread from the original tumour to other parts of the body, or when there is a significant chance that they may have done so even though this cannot be detected.

There are five possible reasons for giving anti-cancer drugs:

- To try to destroy the cancer by the drug treatment alone, aiming for a complete cure (radical or curative treatment).

- To try to shrink the cancer sufficiently to achieve symptom improvement or prolongation of life (palliative treatment).

- To try to improve the chance of cure by eradicating any residual microscopic disease left behind after surgery or radiotherapy, or by shrinking the cancer sufficiently to make these treatments easier or more successful (adjuvant treatment).

- To try to improve the effectiveness of radiotherapy by giving it at the same time (adjuvant treatment).

- To try to prevent cancer developing.

It is essential whenever feasible to monitor the effectiveness of drug treatment when it is being given to a patient with demonstrable cancer. There is no point in continuing with a particular treatment and its possible side effects if it is not achieving the desired result. The effectiveness of treatment can be monitored by assessing symptoms, by clinical examination, by X-rays or scans and by blood tests including for tumour marker levels, depending on the type of cancer and on the particular circumstances.

There are three main categories of drugs that are used to treat cancer: cytotoxic, hormonal (endocrine) and targeted therapy. Cytotoxic (cell poisoning) drug treatment is commonly known as ‘chemotherapy’. Chemotherapy often has a significant effect on normal cells as well as cancer cells, potentially resulting in a variety of side effects. In contrast, hormonal treatments are usually much gentler. However, chemotherapy is active against a far wider range of cancers than hormonal treatment and it also tends to act rather more quickly. Targeted therapies are a relatively recent development. These are medications that have been specifically designed to interfere with particular proteins within the cells of particular cancers that are crucial to their multiplication and malignant behaviour, and in general they tend to be rather better tolerated than chemotherapy.

It is important to remember that it is relatively unusual to be able to predict reliably whether a particular cancer will respond to a particular drug or combination – different people with the same type of cancer will often respond very differently to the same treatment, whether hormonal, cytotoxic or targeted. With some types of cancer and in some situations the chance of a very good response is extremely high, but there are others where the chance is low. However it seems highly likely that in the future genomic testing on a patient’s cancer will become increasingly used to identify those people most likely to benefit from treatment in general and from particular drugs.

It is also important to remember that some anti-cancer drugs can interact with other drugs, and with alternative or complementary medications, including herbal preparations. These can sometimes increase the side-effects of anti-cancer treatment, while under other circumstances they may reduce its effectiveness. The doctor responsible for your anti-cancer treatment should be made aware of any other medication you may be taking.

Many anti-cancer drugs, particularly chemotherapy agents, are administered in hospital. But much treatment is also taken orally by patients in their own homes, particularly hormonal drugs. Unfortunately many people fail to take such medications regularly, exactly as prescribed, and that this can substantially reduce their effectiveness. If you are on such treatment it is very important that you do take it reliably. If for whatever reason you find this difficult you must discuss this with your doctor.

Space here is insufficient for detailed descriptions of drug treatments. Further and much more specific information on the very many anti-cancer drugs, and their use in treating particular cancers, is available from some of the sources listed under ‘Further help’. If you want very detailed information on a particular drug you can usually access online the ‘Summary of Product Characteristics’ produced by the relevant drug company by searching for the name of the drug followed by ‘SPC’. It is important to realise however that the great majority of patients only experience few if any of the large number of possible side effects that are listed for almost every drug.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy works by interfering with ‘mitosis’ (cell division). Just like radiotherapy, if it is completely successful in stopping cancer cells dividing, the tumour will eventually disappear as its cells die of ‘old age’ without being replaced.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy, rather like radiotherapy, is particularly active against both cancer cells and normal cells that are dividing. When chemotherapy is successful, its effect is often seen most quickly in cancers where the cells were dividing rapidly beforehand. Similarly, the side effects tend to be prominent in those tissues or organs where the normal cells are usually dividing quickly. These include the bone marrow where the blood cells are made, the hair follicles and the inner lining membrane of the bowel.

As with radiotherapy, giving chemotherapy involves trying to strike the right balance between killing cancer cells on the one hand, and avoiding intolerable side effects on the other. Fortunately, considerable advances have been made in recent years in lessening the side effects of chemotherapy, which are now much less troublesome than many people imagine. Indeed, some forms of chemotherapy now cause virtually no unpleasant symptoms whatsoever. Somewhat surprisingly, friends and relatives still occasionally lead patients to expect chemotherapy to be much more unpleasant than it really is.

There are many different cytotoxic drugs, working in a variety of different ways. There are now well over 50 drugs in common or quite common usage, and a vast number of combinations of them. They are used to treat a wide range of different cancers and in a wide variety of circumstances. Individual drugs vary considerably in how well they work against particular cancers.

Combining drugs

A proportion of the cells of any cancer may be resistant to a particular individual drug, even if that drug is very effective against the remainder. This is why chemotherapy quite often involves taking combinations of drugs in the hope of lessening the chance of treatment failure because of resistance. Also, lower doses of individual drugs can be used in combinations than might be needed if they were being given singly, and this can sometimes lessen particular side effects.

When prescribing such ‘combination chemotherapy’ your doctor will choose a regimen comprising drugs that are often active against your particular type of cancer, but which have rather different side effects. The chosen combination may also incorporate drugs that interfere with different stages of cell division. However, the regimen will ultimately be based on its track record in treating large numbers of people with the same kind of cancer in the past.

Having chemotherapy

Sometimes chemotherapy may be taken by mouth (‘orally’), but more often it is given by injection into a vein (‘intravenously’ or ‘IV’). Having a chemotherapy intravenous injection started usually feels just like having blood taken for a blood test. You might feel a coolness or other unusual sensation in the area of the injection.

You will probably have chemotherapy intermittently, say once every three weeks, twice a month or perhaps weekly in the outpatient clinic. Usually it is administered as a single injection or ‘infusion’ (using a ‘drip’) into a vein on the hand or lower arm over a few minutes or sometimes over several hours. Sometimes injections are repeated daily for a few days, and sometimes a drug is infused continuously over a day or a few days, with two- to three-week intervals in between courses. There are very many different treatment schedules.

You may need to stay in hospital if you are having more intensive or toxic treatment. Infusional chemotherapy quite often requires you to be treated as an inpatient on the ward, although it is often possible to administer some drugs by continuous infusion at home using a small pump strapped to the body. This method is used particularly for those patients who are treated by continuous infusion over prolonged periods.

If you need prolonged infusions or very frequent injections, or if there is difficulty in getting into your veins, you may have a ‘central venous catheter’ or ‘line’ inserted. These are thin flexible tubes which have their inner end positioned in a large vein inside the chest and the other end outside, so that drugs can be injected into it. The outer end may be on the front of the chest (Hickman or Groshong catheters) or in the arm in the case of ‘peripherally inserted central catheters’ (‘PICC lines’) which are put in via an arm vein.

Sometimes the outer end of the catheter is not brought out through the skin but is attached instead to an ‘implantable port’, a small container placed surgically just underneath the skin of the chest wall. Injections are then made through the skin into the port. These ports are not suitable for everyone, and some patients don’t like having to have a needle put in every time they have treatment, but they are barely visible and they do allow people to engage in many activities, including swimming, with little if any difficulty. All these devices can also be used for taking blood samples.

Very occasionally chemotherapy is given via a catheter inserted into an artery directly supplying a cancerous liver or limb. If a limb is treated in this way it is possible to isolate both the arteries and veins of the limb from the rest of the blood circulation during treatment, and thereby expose the cancer to very much higher concentrations of drugs than would be tolerated if they were being given as conventional systemic treatment. This technique is known as ‘isolated limb perfusion’.

Each individual period of chemotherapy administration, whether given in a single dose or over a few days, is commonly known as a ‘cycle’ or ‘course’, although sometimes single injections or infusions are called ‘pulses’. Chemotherapy injections or infusions are given by specially trained staff, usually by highly trained nurses.

How long does chemotherapy last?

Just how long your chemotherapy treatment will continue depends on a number of factors. When given with the aim of cure or as an adjuvant treatment there will probably be a clearly defined duration (provided of course there is no evidence that it is not working satisfactorily), based on past clinical experience and research. Many courses last from three to six months, but occasionally longer. When the aim is to relieve symptoms or prolong life, how long the treatment lasts depends very much on the type of cancer, the efficacy of treatment and any side effects. Some patients may do best with a finite course of treatment, perhaps 6 cycles over about 4 months, followed by a rest. Others may benefit from continued treatment, particularly if it is well tolerated. If there have been some troublesome side effects the full benefit of treatment may only become apparent after it has finished and the side effects have worn off.

Side effects

These days many people find that chemotherapy causes few serious problems and, although you will probably experience some side effects, these are often not at all severe. They vary enormously according to the drugs and dosage used and your general health. There are, however, some side effects that are quite common to a large number of drugs. The gaps in between treatment courses allow the normal cells to recover, particularly the bone marrow cells, which are generally more sensitive than other normal cells to chemotherapy.

Effects on the blood (and why blood counts have to be checked)

The bone marrow produces the blood cells, of different types. The red cells carry oxygen around the body, the white cells (also known as ‘neutrophils’, ‘leucocytes’ or ‘granulocytes’) fight infections and the platelets clot the blood to seal leakages in blood vessels. A deficiency of red blood cells is known as anaemia. A deficiency of white cells is called ‘neutropenia’ or ‘leucopenia’, and ‘thrombocytopenia’ is a deficiency of platelets. It is worth mentioning that all these different types of cells start off as identical immature ‘stem cells’, which through successive divisions eventually become mature functioning red cells, white cells or platelets. Although the stem cells mostly live in the bone marrow a small number can also be found in the blood stream.

Most cytotoxic drugs interfere temporarily with bone marrow function, particularly the production of white cells and platelets. Bone marrow toxicity is the most common and generally the most important side effect of chemotherapy. The concentration (‘level’ or ‘count’) of the white cells and the platelets in the blood will usually fall during the week or so after chemotherapy, the extent depending on both the drug(s) used and the dosage.

Once neutropenia reaches a certain severity, you are at an increased risk of getting an infection and your immune system is less able to deal with it. For this reason, you will probably be advised to try to avoid close contact with people with infections, and with children who have recently received immunisation with a ‘live’ vaccine. You may also be advised to pay extra attention to personal hygiene, dental and skin care, and to avoid squeezing pimples as this can release bacteria into your bloodstream. Such precautions are especially important if you are receiving particularly intensive treatment. Patients who are having or have recently had chemotherapy should check if it’s all right for them to have any immunisation themselves. They will usually be advised to avoid ‘live’ vaccines (those containing living organisms).

If you are having chemotherapy, you should always tell your doctor immediately if you have any signs of an infection, particularly a fever, chills or sweating. If this happens your blood count will usually be checked straightaway. If your white cell count is below a certain level, you will probably have to have ‘broad-spectrum’ antibiotics intravenously to help your body’s own immune system fight off the infection, while waiting for the count to recover.

Very occasionally, thrombocytopenia becomes so severe that you start to bleed or bruise very easily and, again, you should report this to your doctor promptly. If necessary you can then be given a transfusion of platelets from donated blood while waiting for your marrow to recover. If your platelet count is low you must make every effort to avoid even minor injuries. Anaemia caused by chemotherapy is usually a much less urgent problem. However, it can cause skin pallor and symptoms such as weakness, tiredness and breathlessness.

Normally the blood count recovers fairly rapidly, but it is important that it has returned to normal by the time you have your next course of treatment. If not, it is usually necessary to postpone further treatment until the count has recovered, and sometimes it is then decided to reduce the chemotherapy dosage. If further chemotherapy were to be given when the count was already low, there would be a greatly increased risk of serious complications. This is why your blood count is checked routinely before each course or pulse of chemotherapy.

Sometimes marrow-stimulating ‘growth factor’ (also known as ‘granulocyte colony-stimulating factor’ or GCSF) injections are given after chemotherapy to hasten white cell recovery. On occasions a red blood cell production stimulant, epoetin, is given to patients with troublesome anaemia, but usually this is dealt with more rapidly, simply and possibly more safely by blood transfusion.

Sickness

Nausea and vomiting are well-known side effects of chemotherapy, but they are now much less of a problem than they used to be. Several drugs cause this only to a slight degree, if at all. If you are taking drugs that cause more troublesome sickness, the problem can usually be prevented or greatly lessened by modern antidotes. Anti-sickness drugs (called ‘antiemetics’) are now often given routinely to stop symptoms developing, sometimes starting the day before the chemotherapy is given (see section on ‘Nausea and vomiting’).

Hair loss

Another well-known and common side effect is hair loss or ‘alopecia’, although not all drugs cause it. Hair is sensitive because the cells in the hair follicles divide rapidly. Sometimes alopecia is only slight, but with some drugs it becomes virtually total. Hair loss usually begins about two to two and a half weeks after the start of treatment and short-lived scalp tenderness shortly before the hair starts coming out is common. Hair always regrows once chemotherapy is completed, usually starting to do so about three weeks after the last course. You may find that at first your hair is curlier than before, and this can persist for up to a year or so. Occasionally some regrowth occurs during chemotherapy. Hair loss can occur on all parts of the body, but it is the hair on the scalp that is affected most.

Fortunately, society’s attitude to hair loss has changed considerably in recent years, perhaps partly as a result of changing fashions and partly because we are all more used to seeing and reading about people who have lost their hair after cancer treatment. Although you may well be understandably upset at the thought of losing your hair, you will probably find that in reality you cope with it better than you expected.

If you’re not happy to leave your head uncovered (although increasing numbers of people are), you should choose a wig or hair- piece before your hair starts falling out. It’s usually a good idea to shave off your remaining hair or at least cut it short once it starts coming out significantly.

You may be offered the option of a technique called ‘scalp freezing’ to try to lessen hair loss. It involves wearing an extremely cold cap for some time before and after a chemotherapy injection. The cold causes the scalp blood vessels to constrict, thereby reducing the drug supply to the hair follicles. It’s not suitable for everyone and, although it can work well for some patients, it’s not always successful. It does prolong considerably the time involved in receiving chemotherapy and it can be uncomfortable.

Other side effects

Many people feel a little unwell for a day or two after chemotherapy, or sometimes for longer. Tiredness is also very common and occasionally it can last for some while after treatment. Another common side effect is altered taste, with patients losing their ability to appreciate normally certain flavours in both food and drinks. Many complain of a metallic taste. Most side effects stop fairly quickly, but some can be persistent and very occasionally permanent. Always report any troublesome symptoms during treatment – quite often there is something that can be done about them. Of course, not all such symptoms are in fact caused by the chemotherapy and other possible causes may need looking into.

A rare side effect of chemotherapy is skin damage at the site of the injection. Some drugs have the ability to cause quite serious ulcers if they leak out of the vein into the surrounding tissues. The staff who administer your chemotherapy are highly trained and take the utmost care when giving drugs, but even so this problem can still happen very occasionally. Tell whoever is giving your injection immediately if you experience any pain or discomfort at the injection site while the injection is proceeding, as this may be the first indication of a leak.

Chemotherapy with some drugs can stop the ovaries or testicles working normally. This can result in impaired fertility or infertility, and some women may have an early menopause. This effect of chemotherapy on female fertility can be lessened by administering the hormonal ‘LHRH agonist’ drug goserelin by monthly injections starting before the chemotherapy. Goserelin temporarily makes the patient effectively post-menopausal by shutting down the ovaries and in this quiescent state they are less vulnerable to chemotherapy damage.

Deep-frozen storage or ‘cryopreservation’ of sperms (‘sperm banking’) is offered to younger men about to receive treatment that may render them infertile. Cryopreservation of embryos or non-fertilised eggs are possible options for some women faced with losing their fertility. This requires the use of fertility drugs to stimulate the ovaries to produce eggs which are then removed. This is done using a needle inserted through the vagina while the patient is sedated, the operator using ultrasound scanning to guide the needle tip to the ovary. The eggs are then either immediately frozen, or fertilised in the laboratory by sperms from a partner or donor to create embryos ready for freezing.

There are many other potential side effects of chemotherapy, some being peculiar to particular drugs. However, it’s also true to say that most people either don’t experience them or don’t find them unduly troublesome, or find that they can be satisfactorily treated or even prevented. Most people say that chemotherapy was rather less troublesome than they had anticipated. All side effects are more likely and more severe in people who are receiving more intensive treatment. They include mouth ulcers, sore eyes, cystitis, diarrhoea, nail changes, numbness of extremities, rashes, slightly impaired concentration and memory, and depression. Sometimes sucking ice for about half an hour before and during the administration of chemotherapy can help prevent or lessen mouth ulceration. Very rare side effects from some drugs include lung, heart or kidney damage, and causing another cancer to develop many years later.

Reading about all these possible side effects can be alarming if you are about to undergo chemotherapy, but it’s worth stressing that many people are able to continue with normal life and work for much of the time in between chemotherapy courses. Indeed, those who do so often seem to cope better with it all. For most patients keeping active both physically and mentally will help lessen tiredness, stress and anxiety. It will help keep muscles strong, prevent weight gain and reduce the risk of getting blood clots in your leg or lung, which are potentially serious occasional complications. It may also help the speed of recovery once your treatment is finished. Of course keeping active is not going to be right or possible for everyone, in particular for some people receiving palliative treatment for more advanced disease. If you are unsure you should speak to your oncologist or the nurses giving your treatment.

Stem cell transplants

Sometimes chemotherapy is given in very high dosage, which inevitably affects the bone marrow severely. Such intensive treatment is suitable only for people with some types of cancers, particularly the leukaemias, the lymphomas and myeloma. It has such a profound effect on the blood that the person being treated needs to be ‘rescued’ by being given a transplant of healthy bone marrow stem cells. These cells restore the ability of the body to produce normal red and white blood cells and platelets. A transplant thus makes it feasible to give much higher doses of chemotherapy than would otherwise be possible, thereby improving the chance of a cure for people with some cancers.

If you are having a transplant using your own stem cells (an ‘autologous’ transplant), it must be removed before intensive chemotherapy. Alternatively, it may be taken from a ‘donor’ whose marrow matches yours very closely (an ‘allogeneic’ transplant). A close match is important, otherwise it will be ‘rejected’ later by your immune system. Many donors are close relatives, usually brothers or sisters, but unrelated donors can also sometimes provide marrow that is a good match.

Most transplants are now performed not by removing and replacing actual marrow, but by removing stem cells from either your own or a donor’s blood-stream. These are essentially marrow cells that have been stimulated to leave the marrow in large numbers by injections of growth factors. A drip is put into a vein in each arm. Blood is taken from one arm into a machine that removes the stem cells and it is then returned via the other drip. The whole procedure takes three or four hours. The stem cells are frozen and stored until they are given to you via a drip when required.

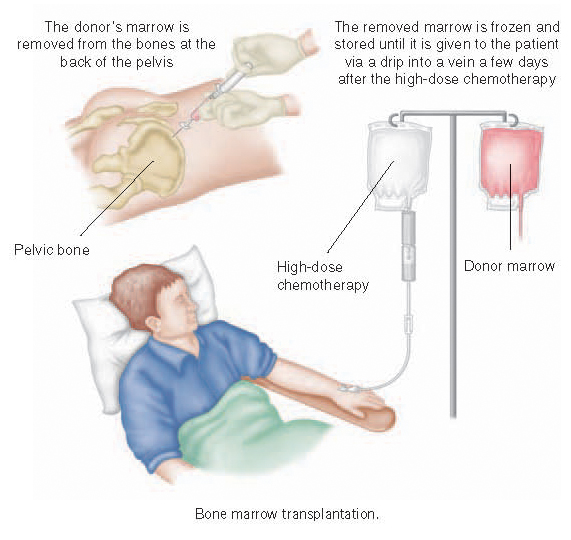

If actual marrow is being used for the transplant, the removal or ‘harvest’ is done by inserting a special needle into the marrow of the bones at the back of the pelvis under general anaesthetic. Only a fairly small proportion of the total marrow is removed, leaving ample to meet the donor’s immediate requirements. It is replaced fairly rapidly by division and multiplication of the remaining marrow cells. The removed marrow is frozen and stored until given to you via a drip after the high-dose chemotherapy. The marrow cells then find their way via the bloodstream to your bones, where they start to manufacture blood cells again.

Sometimes a well-matched donor can’t be found for someone who needs an allogeneic transplant. In this situation blood from the umbilical cord of a newborn baby can be a very useful source of stem cells. After birth the blood left behind in the placenta and the umbilical cord, which is very rich in stem cells, is usually wasted by being thrown out with these tissues. But it can be frozen and stored until needed. The number of stem cells obtained by this method is however less than with the other methods and this technique is currently only suitable as a treatment for children or small adults.

Hormonal treatments

Some cancers depend on hormones for their growth. Hormonal treatments work by preventing cancer cells getting or using the hormones that they need. They tend to have much less effect on normal cells than chemotherapy. However, hormonal treatments are effective only in the treatment of the relatively limited range of cancers that are potentially susceptible to hormonal influences. These are principally those of the breast and prostate, but some cancers of the inner lining of the uterus (‘endometrium’) and thyroid will respond to hormonal treatment. Hormonal drugs are most commonly given in tablet form. All hormonal treatments tend to be more effective against slower growing cancers. They work more slowly than chemotherapy and they may need to be taken for some months for any effect to become apparent.

Breast cancer

The female sex hormone oestrogen can stimulate breast cancer cells to divide and multiply. The chain reaction within the cells that achieves this is triggered by oestrogen molecules first linking up with ‘oestrogen receptor’ proten molecules inside the cells. Hormonal treatments for breast cancer are only prescribed for those patients whose cancer can be shown on laboratory testing (immunohistochemistry) to be ‘oestrogen receptor’ positive. Oestrogen receptors are also known as ‘ER’ because of the American spelling ‘estrogen’. What follows specifically concerns the treatment of breast cancer in women, but rarely breast cancer occurs in men and it too can respond very well to hormonal treatment.

Tamoxifen, taken as a single daily tablet, works by interfering with the linking up or binding of oestrogen to the oestrogen receptor. It was for decades by far the most commonly prescribed drug for women with breast cancer but is now used rather less frequently than other drugs. But it is still commonly used and highly effective for some patients and when given as an adjuvant treatment following surgery it improves the chance of cure. Adjuvant tamoxifen has in the past been recommended to be taken for five years, but recent research has shown that it can be even more effective if taken for ten years. Tamoxifen can also be very valuable as a palliative treatment.

Most women tolerate tamoxifen well, but it can sometimes cause side effects such as hot flushes, slight weight gain and vaginal discharge. Very infrequently it can cause vaginal bleeding. If you develop this you should tell your doctor so that the reason can be investigated. The cause is usually some benign thickening of the inner lining of the womb, but very occasionally there may be an early cancer of the lining requiring surgery.

In more recent years a group of hormonal drugs known as ‘aromatase inhibitors’ have been used increasingly for post-menopausal patients with breast cancer. They are also given as a single daily tablet and they work by inhibiting the normal production of oestrogen by non-ovarian tissue in the body, particularly fatty tissue. They thus subtantially lower the levels of oestrogen in the body and this has an inhibitory effect on cancer cells which would otherwise have been encouraged to grow by the oestrogen. These drugs are not effective in reducing hormone levels to a sufficiently low level if the ovaries are still producing oestrogen, so they are only used for women who have gone through the menopause or for younger women whose ovaries have been removed or rendered functionless by treatment with an LHRH agonist.

Overall the aromatase inhibitors are slightly more effective than tamoxifen when given both as adjuvant and palliative treatments (although for some patients the additional benefit is negligible) and they can also further improve the chance of cure when given as an adjuvant treatment for some patients following a course of tamoxifen. In general these drugs, anastrozole, exemestane and letrozole, are fairly well tolerated but hot flushes, vaginal dryness and mild joint acheing are quite common. They can also cause bone thinning and a bone density measurement is often undertaken to identify those patients at risk – some may need to take additional medication, for example vitamin D and calcium supplements, to maintain good bone health.

There are other hormonal drugs available for breast cancer patients, including toremifene given daily as a tablet, and goserelin and fulvestrant given by infrequent injections. The choice of hormonal drug depends on a variety of factors, including menopausal status and side effects, and whether the treatment is adjuvant or palliative. Goserelin is one of the LHRH agonists, already referred to, which make pre-menopausal women hormonally post-menopausal. The effect is equivalent to a surgical oophorectomy, but only temporary. When used palliatively hormonal drugs can often keep cancers in remission and control symptoms for very long periods, but usually the cancer will eventually become resistant and escape control. However, if a woman has responded well to one of these drugs, there is then quite a good chance that she will respond well to another.

Hot flushes are quite a common side effect in women taking hormonal treatment for breast cancer. Often they are not unduly troublesome, but if they are impacting significantly on quality of life additional treatments are available which quite often lessen them. These include the antidepressant drug fluoxetine, the pain killers and anticonvulsants gabapentin and pregabalin and another drug, clonidine, all in fairly low dosage. There is some evidence that acupuncture can also help. Hormonal drugs are in general probably best avoided.

Both tamoxifen and raloxifene, taken for five years, can now be used to lower the risk of breast cancer in women at high risk of the disease.

Prostate cancer

This type of cancer is usually highly responsive to hormonal treatments that stop male sex hormone (androgen) stimulating the cells to divide. At one time this was best achieved by castration – removing the testes, an operation known as ‘bilateral orchidectomy’. But the same effect can now be achieved by using one of the closely related LHRH agonist group of drugs including goserelin, leuprorelin, and triptorelin, which in ‘slow release’ form can be given by injection just once every four or twelve weeks. Another drug in the same group, buserelin, is given via an intra-nasal spray.

These drugs can, however, occasionally stimulate cancer growth in the period immediately after they are first given. This effect can be blocked by taking one of the ‘anti-androgen’ group of anti-prostate cancer drugs, such as flutamide, cyproterone and bicalutamide, in tablet form shortly before the first injection and for about three weeks afterwards. The anti-androgens can also be very effective treatments in their own right.

Prostate cancers usually eventually become resistant to castration or its drug equivalent. Some patients with advanced disease may then benefit from a newer hormonal treatment, abiraterone, which lowers androgen levels in the body even further. It does this by blocking the production of androgen that continues to take place in (non-testicular) tissues elsewhere in the body.

Hormonal treatments for prostate cancer are usually well tolerated but they can cause loss of sexual desire and impotence. They are quite often recommended for men with more advanced cancers that are not suitable for surgery or radical radiotherapy, but they can also be used to shrink down a primary cancer to try to give the surgery or radiotherapy that is to follow a better chance of success.

Targeted therapies

Targeted therapies are aimed at specific changes within cancer cells that contribute to their ability to divide or spread. Because these drugs have such precise molecular targets they tend not to have some of the side effects common with chemotherapy, or not to the same extent, although they can have other side effects of their own. Tamoxifen is in fact a targeted treatment because of its specific action in blocking the binding of oestrogen to breast cancer cells, but the term ‘targeted’ is generally used to describe more recently designed and developed drugs.

The number of these drugs is increasing rapidly and approximately 30 are currently licensed for clinical use in Europe. Some are relatively small molecules that can penetrate the cancer cell easily but others are antibodies – much larger molecules which stick to the surface of the cancer cell and then disrupt its function. The body normally produces antibodies – complex ‘magic bullet’ chemicals – to target specific invading bacteria or viruses, but it is now possible in the laboratory to manufacture antibodies that target very specific proteins within some particular types of cancer cell. For example, they may interfere with the ability of ‘growth factor’ molecules to stimulate cell division or the formation of new blood vessels to feed the cancer. These drugs can also stimulate the body’s own immune system to destroy cancer cells.

There is an increasing number of encouraging reports of the efficacy of targeted drugs in treating a variety of cancers. But unfortunately cancer cells tend to become resistant to them just as they do to chemotherapy or hormonal treatments. The best use of these drugs may be in combination with chemotherapy or hormonal drugs, or with other targeted drugs. At present the rȏle of the majority of these agents is confined to helping control rather than eradicate cancer, but a small number can increase the chance of cure when added to conventional chemotherapy for patients with some types of cancer. A well-known example is trastuzumab (Herceptin) for people with a particular genetic (‘HER 2 positive’) type of breast or stomach cancer. Another is rituximab for patients with an aggressive type of lymphoma. There have been recent encouraging reports of the potential of targeted drugs in stimulating the immune system’s response to melanoma and in treating advanced thyroid cancer. Unfortunately many of these drugs are highly expensive and their availability is often restricted in situations where their effectiveness seems likely to be very limited.

Other agents

A number of treatments have been developed which are intended to destroy cancer cells using the same mechanisms that the body’s immune system uses to fight infections. White blood cells produce proteins known as cytokines and two types of cytokine, interferon and interleukin, can be manufactured and administered in high dosage by injection to treat patients with some types of cancer. Side effects can be troublesome, for example, flu-like symptoms and lethargy, but these drugs show useful anti-tumour effects in a proportion of patients with some of the rarer types of cancer. These include myeloma, some types of leukaemia and lymphoma, kidney cancer, melanoma and the type of ‘Kaposi’s’ sarcoma that some patients with AIDS develop.

There are drugs that can sensitise tissues to damage by a particular type of light emitted from a special lamp or laser. The light is directed where it is needed following administration of the drug. Laser light can be transmitted down fibreoptic cables that have been introduced into hollow organs and even directly through tissues into deep-seated tumours. The maximum impact of this treatment, known as ‘photodynamic therapy’ or PDT, can be focused accurately and it is proving to be very useful in treating cancers and pre-cancers involving the skin, oesophagus, bladder and lung. It can eradicate completely small superficial growths and it can provide useful palliation for selected patients with advanced cancers.

The bone strengthening drugs known as ‘bisphosphonates’ have for long been used to lessen bone damage and improve pain control in patients whose cancer involves their bones, but these drugs can also exert an anti-cancer effect. It has recently been confirmed that bisphosphonate treatment, particularly the intravenous drug zoledronic acid, can help reduce the risk of recurrence in post-menopausal women who have had potentially curative treatment for breast cancer.

Using vaccines to stimulate the immune system to fight the cancer is an experimental approach that is showing some promising early results, particularly in melanoma, bowel and kidney cancer. It seems likely that in the future gene therapy, currently only experimental, will become commonplace. This involves inserting genes that instruct cancer cells to produce proteins which interfere with the cell’s malignant behaviour. There are several ways of getting genes into cells, including using viruses. There have been some promising early trial results but, as with several other new treatments, its high cost may prove to be at least a partial barrier to its widespread use.

KEY POINTS

-

Drug treatments have the potential to destroy cancer cells wherever they may be

-

There are three main types of drug treatment for cancer: cytotoxic chemotherapy, hormonal treatment and targeted treatment

-

If you are taking anti-cancer medication at home it is very important that you take it reliably, exactly as instructed – if this is difficult tell your doctor

-

It is often difficult to predict the response to drug treatment

-

Anyone who is having chemotherapy should report any fever very promptly

-

Many people these days find that chemotherapy causes fewer problems than expected

-

Most patients experience few if any of the large number of possible side effects that are listed in the comprehensive information available for every drug

-

Most patients will benefit from keeping active during treatment

-

Let your doctor know what other drugs or medications you are taking, including any herbal preparations